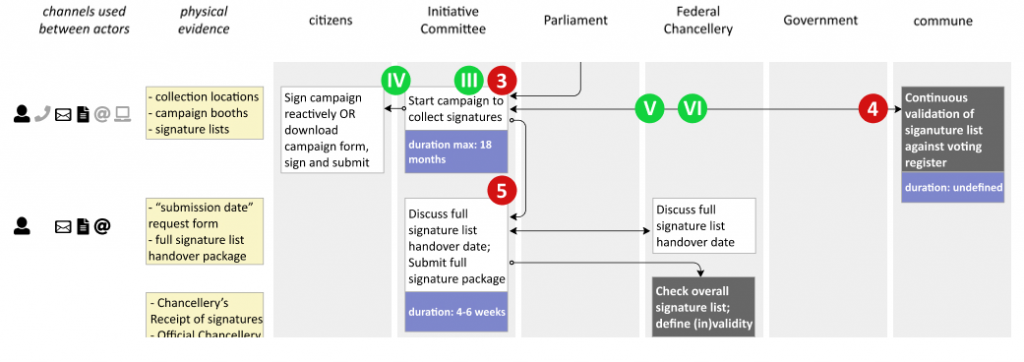

As shown in the previous post, I did a service design analysis of Swiss direct democracy, to really get into the details of how co-creation is done from a citizen perspective. You can find the multi-stakeholder service blueprint here. In this post I want to highlight some breakpoints, delights, and unofficial improvements to the process.

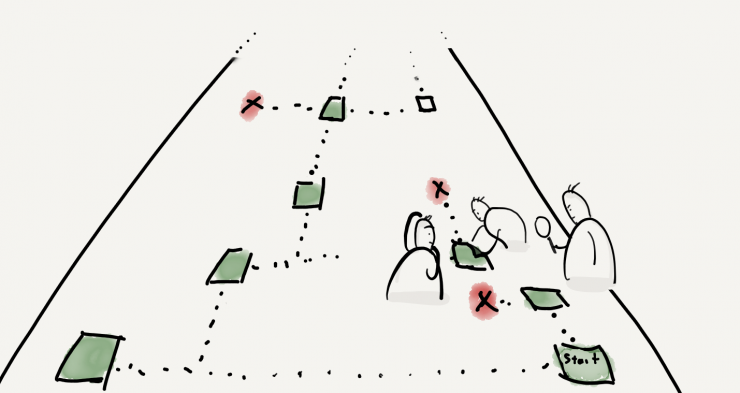

I highlighted 12 breakpoints, 2 points of delight, and 7 unofficial improvements. Let’s zoom in to 2 parts of the service blueprint: collecting signatures, and voting.

Collecting signatures

Here I just want to highlight the breakpoints. These are marked in red in the entire process flow. Citizens need to collect 100.000 signatures if they want their constitution-changing proposal to progress to a referendum.

- (3) Signatures need to be collected on paper, and sorted by municipality. This puts a huge logistical and financial load on grassroots groups that want to initiate such a referendum.

- (4) Verifying signatures is the task of individual municipalities. This verification process is one of the very few actions without a time-limit. This means uncertainty for the initiators of constitution change. There is even an official form to say “hurry up with that verification!”

- (5) when all signature are collected, the initiators need to drop this off at the parliament building. At this point, Initiators lose ownership of Initiative, and have no further influencing power. “It is not theirs any longer – it is the state’s”. This loss of ownership is accepted – yet it is still a breakpoint, as Committee still has a few tasks in the future.

I argue that in such an important process, intentional obstacles need to be part of the system (people are trying to change the constitution – that’s a big deal!). But intentional obstacles do not need to be made operationally difficult. Collecting 100.000 signatures is a big enough task.

Voting

Referendum voting is of course a crucial moment, and accordingly has a breakpoint, an unofficial improvement, and a delight attached to it,

- (11) the breakpoint is that the 3-4 week period of the referendum is the first time for most citizens that they hear about this specific initiative. Initiatives are sometimes symbolic and simple. But sometimes they are very complex, and hard to understand even for economists or politicians, let alone laypeople.

- (B) This is where one of the ‘delights’ comes in. The state informs citizens about the initiatives in a red booklet – a document shared with every citizen. This is a very well structured document that gives a bird-eye view, as well as full details about the initiative in question. It does a great job at explaining what there is to know. It deserves a closer look – see next post.

- (VII) But some civil organizations believe that even this red booklet is not enough to inform citizens about the topic they need to vote on. They want to make it even easier for people to make an informed decision, and thus provide arguments, counterarguments, simplified explanations, visualizations, etc. to better explain the topic. While of course pressure groups will often campaign for their own view, many organizations actually argue for both for and against an initiative – now that’s democracy!

[…] […]