These few posts are an organizational analysis of Swiss direct democracy.

Aaaah, I love processes! Brace yourself, this is a bit longer, but very interesting part. You might think that in a democracy, elections are the most important. Well think again! In Switzerland, referendums are the most important. Switzerland has had more referendums than the rest of the world put together! In the interest of sanity, I will only focus on this referendum aspect of processes. You can ask me about other processes in the comments 😉

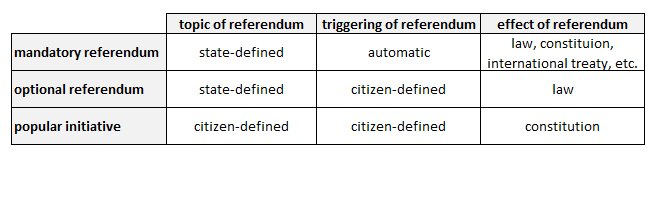

There are three types of referendums. See overview below, and more detail underneath. All referendums are binding, and usually require a simple majority to pass.

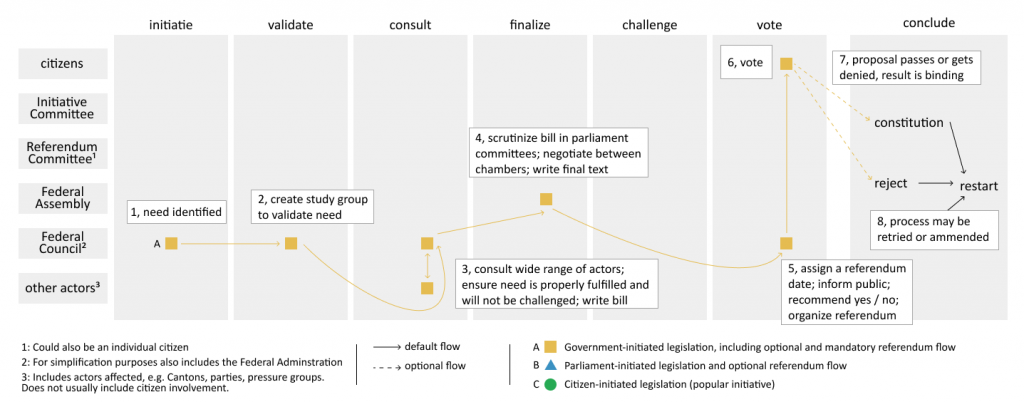

Mandatory referendums are the simples – a mandatory citizen approval on topics such as revision of the constitution, joining an international organizations (EU, NATO, UN, etc.), or introducing urgent federal legislation. If a referendum question is rejected, it may be voted on again at a later date. Here’s the multi-stakeholder flow:

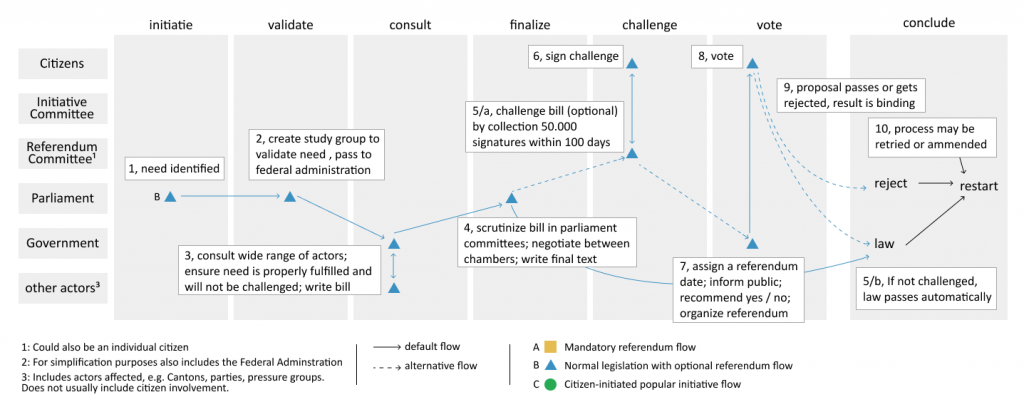

Optional referendums are more complex. This is a check on the state by citizens. Any law made by parliament can be challenged in a referendum by an alliance of eight Cantons, or by any one single individual citizen, or a group of citizens (Referendum Committee). To launch the referendum, 50.000 signatures (around 1% of Swiss voters) are required within 100 days after publication of the law in question. Fear of a law being challenged forces the state to conduct thorough consultation with a wide range of organizations during legislation process. If challenge is successful, the law does not come into force.

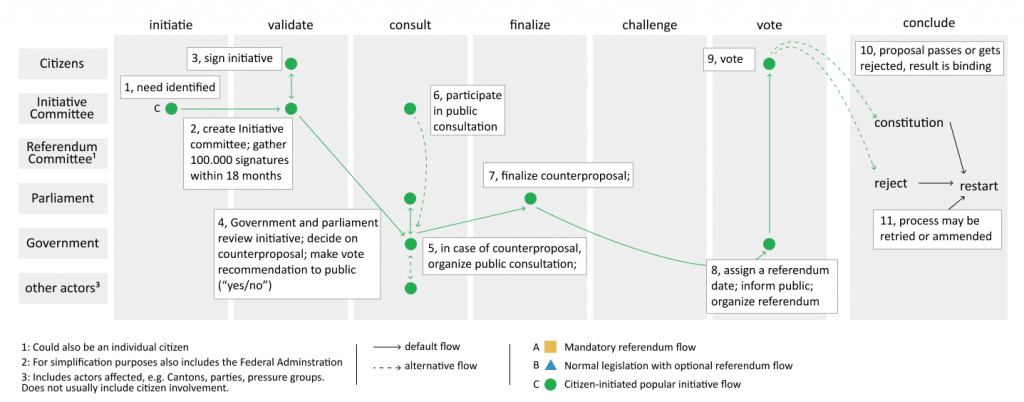

Finally, popular initiatives are citizens’ ability to amend the constitution. Whaaat?! Yes! A group of citizens (Initiative Committee) can define almost any topic on which they want to hold a referendum. Launching the referendum requires 100.000 signatures (around 2% of Swiss voters) to be collected within 18 months. If this is successful, and the referendum itself is successful, the constitution is changed! Crazy! (Sidenote: Parliament and government can provide a counterproposals – more on this later. Suffice to say it is mindbogglingly complex.)

Here’s what the multi-stakeholder map of popular initiatives looks like:

Referendums happen 4 times per year, at pre-set dates, always on a Sunday. On average there are 2-5 federal questions in one referendum, plus a some cantonal and municipal questions. Answers to referendum questions are a simple yes/no. Almost any topic can form the basis of a referendum…even stuff like abolition of the army (did not pass).

The state is required to provide information on referendum questions in a very well organized manner. More on that later. This requirement to inform citizens is taken so seriously that results of a referendum were invalidated in 2019, when a factual error was discovered in the information provided by the state.

Voting is voluntary, with no minimal turnout requirement, and voters become automatically eligible when they turn 18. People can vote in person, via post, also from abroad, and in some cases even by proxy (e.g. family member) or online .

It should be noted, that in urgent scenarios, state can suspended citizen involvement for a limited time via an “urgency procedure” – in past decades this ‘escape route’ of the state has been cut back considerably, and now can last only one year.

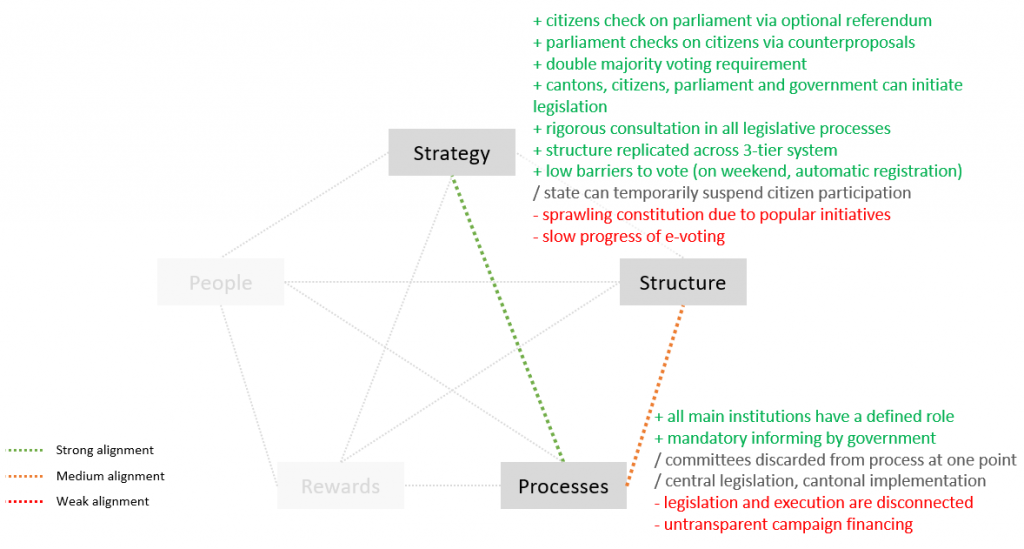

Overall, Processes align strongly with Strategy. A notable side-effect is that the Swiss constitution has turned into an “unsystematic charter, a collection of important principles as well as of rather unimportant regulations”, needing a total revision in 1999. Processes generally align with Structures too, but financing and a disconnect between legislation and execution are strong misalignments.

[…] […]

[…] […]

[…] There is a process in Swiss Direct Democracy called ‘Optional Referendum’. This enables any citizen to reactively challenge laws and regulations once they are issued by the parliament. Let me restate that: the parliament issues a law, and you as an individual have the right to say “Neh, I don’t like it”. Then you need to start collecting signatures to prove that you are not alone with this opinion. I already wrote about this in the organizational analysis. […]

[…] acceptance of an initiative, a lot of wiggle room is left for both legislative and executive branch in how it gets implemented. […]

[…] timeboxing, just look at the one part or the Swiss process where no time limit is applied: If an initiative succeeds, and thus the constitution is changed, a law should follow, to make the spirit of the […]